I woke up this morning, rolled over to face my windows, and was buried in sadness. I will only wake up here, in this bed, in this apartment, in Trastevere, in Rome, on two more mornings. I have had this feeling before, leaving Andover for good at graduation, but then I at least had been preparing. I counted down the days and, with friends, savored the last moments. Here, though, this way of life has become so natural (and we have been kept so busy) that I forgot to mark time. The fact that I would need to leave slipped my mind entirely.

I do have some buffer trips to take the edge off of my departure; on Saturday, I will set out from Rome on a 10-day set of adventures around the north of Italy (more info on that to come). But as I wallowed in my sheets a few hours ago and thought about my last two classes (today and tomorrow), I realized that I haven’t shared almost anything about the work that I’ve been doing while here. Somehow, my bakery‘s cannoli managed to steal the day.

So here’s a tribute to the work that I’ve done, and to this class – the reason that I am here in Rome in the first place. Through “The City of Rome,” I have met two knock-your-American-socks (or, more accurately, your American flip flops!)-off professors; had three guest lecturers who are all experts in their fields; read the vast majority of 16 different books (page count to come later); seen one parade and one set of fireworks; visited about 35 different assigned sites around the city outside of class (never mind the ones during class); written three writing assignments; and (drum roll please) completed a final project and its corresponding 14-page paper. In other words, for those who have been secretly assuming otherwise, yes, I have been doing work.

Final project, you say? What was your final project, Jess? Well, that’s a great question, because I am a very big dork and would love to tell you all about it. However, I am telling you now, if you are NOT a big dork (or are merely reading this blog to laugh at me and my cross-cultural foibles and fumbles), STOP HERE. THE LAND OF ACADEMIA IS FAST APPROACHING. U-TURNS FULLY ALLOWED. You can’t say I didn’t warn you.

Anyways, as I was saying, each person in the class had to do a big research project that culminated in a 20-minute-long presentation and a large paper. We had a lot of leeway about our topic with the major stipulation being that we had to study something that could not be easily learned outside of Rome. In other words, the place and the physical resources of Rome had to be integral to our work.

From the beginning, I was torn about what to do. I researched everything from modern politics and social services to graffiti and the histories of specific roads. I then proceeded to rule out all of my initial options because we were either already covering them as part of our seminar or because they were too hard to do with my minimal skillset (in other words, without speaking Italian). I ended up between two ideas — one, a complicated retracing of Rome as a literary landscape through the words of some of my favorite poets, and two, an urban studies zeroing in on one particular moment of Rome’s urban planning. My professor made the final decision easy from there: I would get to do a mini-presentation on Byron during the fourth week of class (thus my late night expeditions with Childe Harold), and I would focus on my urban studies approach.

I researched feverishly until I narrowed down even further — I decided to do my project on the urban planning that happened in Rome as a direct result of it becoming the national capital of unified Italy in 1871. Prior to that time, Italy was just a collection of disparate regions and Rome was known as the Papal States; after it, Rome was once more on the international map. In truth, though, I chose the city planning underdog. Almost no one agrees with the decisions that were made during those years, and even fewer like the monuments erected to the new nation within the city walls. So I set out to make them care about it anyways.

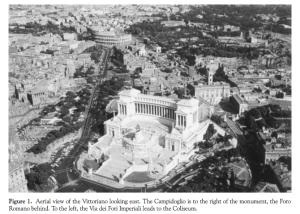

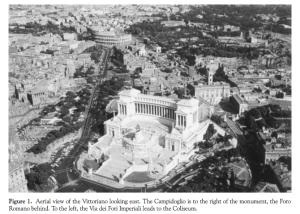

I was the second person out of our group of thirteen to give my presentation. I did it on-site, right in front of the Victor Emmanuel II monument, a huge and generally abhorred building in the middle of Rome commemorating the national unification and the second king of the new Italy. I used that building as a jumping-off point to explain the rest of the urban planning changes between 1871 and WWI; you might remember it as the huge white building from the day of the parade. It made for a pretty impressive backdrop.

Me in the process of presenting. Note that no rotten tomatoes have been thrown at me yet - a clear sign of success.

And, again with my warning firmly established, I am attaching here a full version of my 20-minute-long class presentation. These were my notes. Obviously, I lightened them up, made a lot of silly hand gestures, departed from the script in many places, and answered questions as they occurred, but if you are at all interested (or if you need something to read to help you fall asleep! My blog is happy to help in ALL situations), here’s the gist of my research during these five weeks.

—

For this presentation, I’m going to ask all of you to do something a little cheesy, perhaps, and move with me to the year 1871. I can now address all of you, as citizens of Rome, for the first time since the days of empire as “friends, Romans, and countrymen,” for you are all now part of the newly unified nation of Italy. You are also already residents of the nation’s capital city: that is to say, Rome.

You’ve been anticipating Rome’s new status for a while now. After all, you heard the reports from Cavour’s speech to the Florentine House of government back on March 25, 1861, in which he said:

“The choice of the capital has been determined with great moral reasoning. Here, oh gentlemen (and ladies), agree that in Rome there occurs all the circumstances of history, intellect, and morality for it to be determined as having the condition of the capital of a great State. Rome is the only city of Italy whose memories are not exclusively municipal, as all the history of Rome, from the time of Caesar through the present day, is the history of a city whose importance extends infinitely to all the territories; of one city, that is, destined to be the capital of a great state. I am convinced, deeply convinced, of this truth.”

In fact, despite your pride in your home city, you may have laughed in hearing that. For as noble as your history is, you also know the truth of your hometown, and that is one of grime, decline, and an insular way of life. In fact, just last year, on December 27, 1870, the Tiber had its worst flood in a long time, so intense that it was recorded on the walls of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva and 46 other buildings with red lines at the high water marks, a calamity that our dear Pope Pius IX called divine punishment for the sacrilege which had deprived the Church of its worldly possessions. When our king, Vittorio Emanuele II, entered his new and shining city on December 31, he found it with flood waters covering the low-lying streets, stinking with mud and refuse. A police officer from Genoa, one of the first government servants to arrive in Italian Rome, came with high expectations during his first visit, and left sating, “The impression [the] environment made on me was disastrous. I was confused to see the entrances of the [train] station full of filth, the streets leading to the centre almost dark and blocked by ruins and hedges of vegetable gardens, people laying on the steps of the churches.” You also know the truth of its size – the fact that it no longer reaches anywhere near to the Aurelian Walls, that most of you live crowded in the bends of the Tiber, and that, despite the recent construction of a transportation station called Termini far away from you, most of the surrounding area is full of farmland and ruins; there is a cattle market in the Forum. And then there’s the fact that Rome is only the fifth largest city in Italy at this point without much in the way of infrastructure; because the physical reasons for making this into the capital city are so lacking, you know already that it is the symbolic weight of your city that has propelled it to a position of such importance.

Alright, so why start my presentation at this moment? Why ask you to think as a Roman? Why do a presentation on Rome turning into the capital of unified Italy at all? As an urban studies student, I knew that I wanted to research Rome at a point of physical transition. The changes made to the city after unification fit that criteria, but they also appealed to me for other reasons. First, unlike perhaps the changes under emperors, popes or Mussolini, they happened without the guidance of one central ruler and instead were the results of a series of compromises among various parties. Second, and probably more importantly in my own mind, the vast majority of the literature on Rome’s urban planning treats this time period as open space, junk time, a mere filler between the Church and Il Duce. I disagree. I find this to be one of the most interesting eras of Roman planning because it catches Rome right in the act of juggling its multiple identities – here, a mere municipality with the responsibility to house and feed its citizens. Here, a ring around the newly retreated center of Christendom that needs to deal with a void of authority. And here again, a national capital with international import that needs to live up to its history on the world stage.

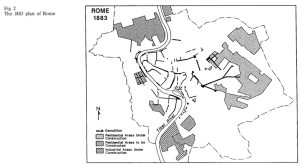

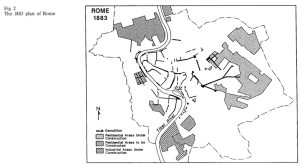

During the years that we are talking about today, Rome tripled in size – from a little pocket of 212,000 people in 1871 to a bustling and sprawling city of 660,000 in 1921. On the bottom of the first page of your handout, you can see some of the proposed changes during that time, and get a sense of the overall volume of growth.

This is the second draft of a plan for Rome, made in 1883. All of the shaded areas are designated for construction. This shows you just how tiny Rome had become under the popes and how much it was about to grow in its quest to become a major European capital city. (Wait? Serious and scholarly captions from Jessica on her blog? Yes, indeed. The world must be ending.)

I’d like to spend today talking about what else changed in the city during that time and the ways that those changes broke with tradition, sometimes to the detriment of the native Romans. I want to argue that the city changed from one thinking about its own immediate well-being to one concerned more with the nation’s ambitions, and articulate some of those ambitions more specifically. I will do this through the lens of this monument and, though the changes that were made here, extrapolate about the changes going on in other parts of the city.

The monument that I studied.

We have talked about this monument before in class and referred to it by its proper set of names – Vittorio Emanuele II, Il Vittorio, the monument to Victor Emmanuel II. But outside of class, we have also heard it referred to by a different set of names: the wedding cake, the typewriter, the confection, the eyesore. Even our beloved Blue Guide calls it “rather ugly” and states, “It can only be described as a colossal monstrosity.” Now, assuming that no nation aims to have its core monument be compared to a pastry shop, let’s step back from our criticisms for a moment to examine why anyone thought this structure was a good idea in the first place. Let’s think about the message that it is trying to send.

When Vittorio Emanuele II, the king of unified Italy, died in January of 1878, a commission was immediately established to raise a monument in his memory. It held an international competition, which, the first time around, was won by a French architect who proposed an arch of victory close to the new train station. Cries of dismay from citizens about the fact that a Frenchman would be designing the Italian national monument quickly led to a revocation of his victory and a reopening of the competition in 1882.

This time, just to be safe, the commission put forth a set of requirements for the monument, all carefully thought through. First, the monument had to be situated in Piazza Venezia, the piazza we see in front of us now, and located on the northern slope of the Capitoline Hill. By doing that, the monument was guaranteed to sit – thwump! – right next to all kinds of symbolic centers of the Roman empire such as the Forum and the Colosseum. Not to mention the importance of siting it on the Hill itself, the place that had hosted the unsuccessful Roman Republic in the mid-fourteenth century when it tried to resist the Papacy. The national government was establishing continuity between the monumentality and success of the Roman empire and the monumentality and success to come of the unified Italy, and it was also creating a clear divide between its own rule and that of the papacy. Sure enough, other aspects of the monument’s location also help to minimize the Church’s authority over the city. It quite literally severed part of the city’s attachment to the Church by demolishing the medieval cloisters of the church of Ara Coeli to allow it better access to the hill. This is one of the instances where we can see a trend across the city during this point in time of church buildings being commandeered, converted, or razed for nationalist planning under the Expropriation Act of 1865, which awarded the municipality of Rome with about 17,000 acres of Church land and about 80 buildings. When the Vatican registered its formal complaint against this practice during the public debate over the city’s Plan of 1873, stating that because churches were public spaces, they were not subject to that law, the council ignored it.

To further illustrate its superiority over the church, the monument placed itself in the main travel artery, Via del Corso, that pilgrims traditionally used to get into Piazza del Popolo and across to what was now the independent Vatican. This reminded pilgrims, or so thought the king, of the secular power of the Italian government before they came into contact with the claimed temporal supremacy of the Pope and provided a tall, corner-filled alternative on the skyline to the dome of St. Peter’s. The monument quite literally put the history and goals of the new Italy on the map.

This placement on the roadways also did something very clever to the overall balance of the city. If you’ll look at the second page of your handout for a moment, you can see the traditional axis of power in Rome under the Church – the cross of the basilicas and the Pope’s major seats in the city.

The cross-shaped axis of the major sites of Papal power in Rome.

Now, look below it. Look at where members of the government choose to place their new buildings – as a direct challenge to the prior axis. Here, we have a trinity that recenters the city with Victor Emannuel at the center, government buildings in the East, including the Quirinal Palace, which the government took from the pope, and Palazzo di Giustizia near the Tiber, right on the heels of the Vatican.

See how the nationalists built into the corners of Rome (see the Vittorio Emanuele in the south, the Quirinale Palace in the East, and the Palazzio di Giustizia or Palace of Justice in the West)? Does anyone else think this is SO INTERESTING??? No? Okay. Well, I guess this is why I am one of very few people concentrating in urban studies...Trust me, though, it's actually pretty crazy. (DORKFEST)

This new axis was reinforced through the building of roads; Via Nazionale, which was originally begun by Pope Pius IX as Via Nuova Pia, made a large pathway between the area of the government buildings and the train station and the monument, while Via XX Settembre, converted from another road started by Pope Pius, would create a similar radius across the city. These roads did much the same as ancient Roman roads in reminding the populace through improved traffic and strategic redirection of the power of the authorities. Further infrastructure was built as walls along the Tiber, which I won’t talk much about now but am happy to answer some questions about at the end if you are interested, and bridges across the river, and there were excavations and recovery of many antiquities along those roads. This is the beginning of this monument as the center of traffic in the city. As a sidenote, this is also a great moment to talk about one of the negatives of these changes for the residents of Rome itself; Via Nazionale was the result of a lot of land speculation by the Belgian cardinal De Merode, who acquired these lands in about 1867 and then came up to the Italian administration to suggest building a road there. This kind of speculation went unregulated by the overwhelmed municipal authorities and meant that many of the basic services that the populace needed, like affordable housing, went unbuilt.

When we look at the actual monument itself, we immediately observe the aspects of it that remind us of ancient Rome. The statue on the horse, which Ashley began her presentation by referring to, indeed echoes a series of heroes in Roman culture, and this is not an accident – the commission required that the monument contain “an equestrian statue with architectural backdrop and suitable stairs.” Giuseppe Sacconi, the Italian architect who ended up winning the commission, recognized this as a desire for a return to Roman ideals and set up the remainder of the space in a massive echo of the most successful monuments of years past. On the first level, he places an altar to Dea Roma, the goddess of Rome, in a nod to the same figure on the top of the Capitoline Hill. The second level continues that acknowledgement of Michaelangelo’s design with the equestrian statue. On the third level, he brings back the portico and columns that mirror those in the nearby Forum and inscribes secular declarations saying “Of the citizens” and “Of the nation.” There is purposefully no inclusion of God here, nor saints; instead, at the top of the columns, where the saints stood in the piazza outside of the Vatican, a series of classical figures in togas strolls by. And, since we have talked so much about building materials, I have to mention that the whole building is made out of white Brescian marble, material quarried in Italy and going back to the blazing white color of the old monuments in the face of hundreds of years of colorful medieval and Renaissance streets. Local materials, local architect, local symbols – this is pure nationalism.

The irony of the architecture is that much of it comes from a Beaux Arts style that was all the rage in Europe at the time. This mixed Renaissance, Baroque, Greek, and Italic motifs in an over-the-top fashion that can be seen here as well as on the Palazzo di Giustizia. Thus, despite the authorities getting into a tizzy over accidentally letting a French architect win the first contest, this “authentic Italian monument” still ended up being an agglomeration of other nations’ influences.

Once they were in the process of building this monument, Italian officials began immediately to think of how best to show it off. After all, as we mentioned before, if you want to make the new state of Italy the center of everyone’s thoughts, the best way to do that is to place it at the center of their physical space. Prior to this monument, Rome was a city with several concentric hubs of activity, all pushing forward at different periods in time – St. Peter’s Basilica crossing over to the other three major churches in the city, the Tiber River, the Forum, the Capitoline. When the committee in charge of this monument opened their second competition, they knew that they wanted to do from a city planning standpoint what they had already done politically and unify the corners of the city into one place. This needed more than the aforementioned roads – it needed a red carpet runway that would emphasize the grandiosity of the space. To create that, they took what was little more than a narrow opening in this space and started demolishing with a vengeance. They knocked down much of the immediate district, including a medieval tower of Pope Paul III. They took apart the Palazzo Torlonia and the Palazzo Venezia, both of which stood in the area of the desired Piazza Venezia, and rebuilt them with the Torlonia on the eastern side as a mirror of the Palazetto Venezia, which was rebuilt brick by brick one hundred yards to the west. The only two buildings that survived were a part of an ancient tomb on the northeastern corner and an old House of Giulio Romano. Both structures are ancient Roman in origin and thus we can see that through their choice of what to preserve, the new leaders of Italy wanted to establish that line between themselves and the last days of strong and vibrant government in Rome.

It is important to note, once again, the negatives of these choices. For the Romans lost, rapidly and without any kind of collective permission, much of the city’s character during those years, and much of its antiquities. Rodolfo Lanciani, an archaeologist who served as Director of the Excavations of Rome in the 1870s, admitted in response to the disappearance of porticoes, temples, basilicas, and villas across the city, “It would be of no use to deny that all these great conquests in the artistic and scientific field have been obtained with a certain amount of loss and sacrifice. But we must always remember that Rome has always lived at the expense of the past.”

This is the note on which I want to begin ending my presentation – right with that statement of ambiguity. Indeed, Rome has always had to stand over its own shadow, and this monument was just one more attempt at a specific moment in time to conquer the past and make it serve the present. Why did this particular monument fail to inspire? I’ve thought a lot about this, and a lot about why the urban planning happening around the monument also failed to make the impact that the nascent Italians were hoping for. Certainly, part of it has to do with the fact that it seeks to establish continuity not with its neighboring time periods or buildings, those of the medieval period and the Renaissance, but with the ancient empire; thus, its use of white marble, which would have been so appropriate back then, sticks out like a sore thumb. One article called this inability to create continuity with the historical pieces around it the monument’s “myth of a unified past underwriting a unified future.” It reminded me, in fact, of ill-fated Cola di Rienza in his attempts to revive an old glory that ended in failure with him memorialized halfway up this neighboring hill. Moreover, this monument is one that seeks to try to prove something not just to its citizens but to Europe at the time; it wants to fit itself in with a collection of changing capital cities, especially Paris with its famous boulevards and triumphal arches, and for this, it gets constructed in a style that is too overwrought for its size. It made me think of Hadrian’s villa, and his understanding that his worldly influence could go wild in his own space but must be tempered in his other buildings to fit in with the urban landscape; I don’t think that Giuseppe Sacconi had this insight. Third, despite being placed on the Capitoline Hill, the monument is just that: a lump of decoration placed on top of a hill. Unlike the famed fountains of Bernini, which used the varying elevation of the city to create different types of fountains, or the Capitoline Hill, which makes space with Romulus and Remus visible right next to a view of the city, I don’t feel as though this monument works with the natural landscape or the topography of the city well at all.

The "lump" of the monument as seen from above. Note how it doesn't fit in with the surrounding landscape, and also check out its strategic positioning in the imperial core of the city, with the Forum and Colosseum right next door. Mussolini would later take advantage of this and build a road from the monument straight through to the Colosseum as a sign of empire.

Finally, I’d like to argue that much of the frustration with this building started with frustration with the national government at the point in time when it was built. As Rome’s municipal authorities were working to put forth two city plans, the second in 1883, the national government refused to give them the necessary funding to carry out the changes. Instead, it paid only for the buildings (such as the palace of justice) that it desired and not those that would benefit the city as a city instead of the city as a capital. You can see this sense of frustration echoed in a contemporary cartoon depicting Rome being raped by the national government:

A personified Rome being stripped of its dignity by the national government

This, combined with the land speculation that I mentioned above, meant a lack of affordable housing, at least forty thousand slum dwellers who had been driven off by clearing, and a sense of minimal progress on the larger city picture. All of this as this monument and the destruction preceding it was taking place right before the city’s eyes.

I want to conclude by reemphasizing my belief that this small chunk of history, the period between 1870 and the start of World War I, is a time of crucial change for Rome. Through this monument, we can see that even the smallest choice was ripe with reasoning and consequences, and we are reminded that urban planning – and the planning of monuments – is one giant attempt to turn space into power.

Tags: academia, cities, italia, monuments, nationalism, Rome, the hills of rome, urban studies